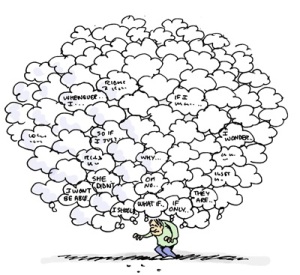

In this blog we will look at something which we believe is apparent in alcoholics, the decision making difficulties very present in active alcoholism and to a lesser extent in recovery.

By this we mean there is a tendency to use the short term fix over more long term considerations, a more “want it now” than delayed gratification. This may be down to internal body (somatic signals) which can give rise to an unpleasant feeling at times prior making a decision, as if we sometimes make decisions based on a distress feeling rather than forward thinking, that we choose a decision to alleviate this feeling. It has been suggested by some authors that emotions do not guide the decision making of alcoholics and addicts properly and this is the reason why they are maladpative.

Equally it may be that certain somatic states such as the so-called ‘primary inducers’ of feeling, mainly centring on the “anxious” amgydala which helps in our responding to body states associated with chronic drug and alcohol abuse, such as alleviated, chronic stress (and it’s manifestation as emotional distress) have the potential to dominate decisions, to treat decisions in a habitual, automatic manner and not in via a thoughtful consideration of the possible outcome of our decisions.

Once science thought we make sensible reasonable decision based on pure reason but it has become clear in recent decades that we use emotional signals ,”gut feelings” to make decisions too.

It appears that if we don’t access these emotional signals we are destined to make the move decisions over and over again, regardless of their outcome and consequence.

The extreme example of emotions guiding decisions, would be running from a rampaging lion, this decision is make emotionally, via the quick and dirty route, the “low road” according to Le Doux. The amygdala, which directs signal traffic in the brain when danger lurks, receives quick and dirty information directly from the thalamus in a route that neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux dubs the low road.

This shortcut allows the brain to start responding to a threat within a few thousandths of a second. The amygdala also receives information via a high road from the cortex. Although the high road encodes much more detailed and specific information, the extra step takes at least twice as long— and could mean the difference between life and death.

Emotional dysregulation and altered reward sensitivity may underpin impulsive behavior and poor decision-making.

Both of these tendencies can be seen in the “real-world” behavior of addicted individuals, but can also be studied using laboratory-based paradigms.

Addiction is associated with a loss of control over drug use which continues in spite of individuals’ awareness of serious negative consequences.

Increased reward alone, as seen in alcoholics and resulting in attentional bias and automatic responding to cues (internal and external) do not seem a sufficient explanation for this persistent maladaptive behavior of addiction.

Instead there must be additional deficits in decision-making and/or inhibiting these maladaptive behaviours and which critically involve emotional factors exerting a detrimental effect on cognitive function.

The term “impulsivity” is often used to describe behavior characterized by excessive approach with an additional failure of effective inhibition (1) and has consistently been found to be associated with substance dependence (2,3).

Impulsivity is a complex multifaceted construct which has resulted in numerous additional definitions such as, “the tendency to react rapidly or in unplanned ways to internal or external stimuli without proper regard for negative consequences or inherent risks” (4), or “the tendency to engage in inappropriate or maladaptive behaviors” (2).

This we suggest could be the consequence of either the push or pull of dsyregulated emotions.

By this we mean we either do not use emotions properly to feel the right decision as we cannot process them properly to use them as “guides” in decision making or these dsyregulated emotions become distressing and prompt more compulsive decision making, effectively to relieve the distress of these negative emotional states.

Either way it appears that not only do alcoholics, but also children of alcoholics, use a more motor-expressive style of decision making, i.e. they recruit more compulsive regions of the brain rather than prefrontal cortex areas normally used used to make planned, evaluative decisions.

It appears that emotional dsyregulation is at the heart of maladaptive decison making in alcoholics and addicts.

Distressed Based Impulsivity?

Emotional impulsivity more closely reflects the interaction between emotional and cognitive processes. Negative urgency, the disposition to engage in rash action when experiencing extreme negative affect (mood, emotion or anxiety), or in simple terms, distress-based impulsivity, was found to be the best predictor of alcohol, drug, social, legal, medical, and employment problems (5).

Substance users frequently make decisions with a view to immediate gratification (6-10), and may be less sensitive to negative future outcome (‘myopia for the future’) (11,12). It has been hypothesized that substance users are less able to use negative feedback to guide and adjust ongoing behavior (12).

These findings highlight a specific role for emotion.

Emotional impulsivity traits appear distinct from other impulsivity traits and particularly pertinent for dependence, reliably differentiating substance users from controls, and also predicting poorer outcomes in dependent individuals.

The impact of emotional processing on cognitive performance.

A common behavioral measure of impulsivity is the delay discounting task which measures the degree of temporal discounting. Participants are faced with the choice of a small immediate reward, or a larger delayed reward; choosing the smaller immediate reward indicates a higher degree of impulsivity.

Increased discounting of larger delayed rewards has been found in heroin- (13), cocaine- (14), and alcohol (15 -17) -dependent individuals.

Enhanced discounting is also seen during opiate withdrawal, possibly reflecting the emergence of negative affect states during withdrawal (18).

Withdrawal is a period of heightened noradrenaline ( a “stress” chemical”) and this excessive stress has a bearing on decision making, and in relapse.

High levels of negative affect, anxiety/stress sensitivity a in substance dependent individuals may therefore contribute to observed deficits on decision-making tasks. Stress mechanisms are considered to be important mechanisms underlying relapse (19), suggesting these emotional traits impair real life decision-making.

Studies directly assessing the role of emotional states on decision-making in opiate addiction have shown that trait and state anxiety are negatively correlated with performance on the the Iowa Gambling Task – IGT (20). Furthermore, stress induction using the Trier Social Stress Test, was shown to produce a significant deterioration in IGT performance in long term abstinence and newly abstinent heroin users, but not in comparison subjects.

Treatment with the B adrenocepter antagonist propranolol blocked the deleterious effect of stress on IGT performance, supporting the role of the noradrenergic system in the generation of negative emotional states in substance dependence (21).

These findings indicate that conditioned emotional responses, i.e. stress based emotional response, impair decision-making.

The impact of emotion on impulsive action and decision making

Planning systems (also referred to as deliberative, cognitive, reflective or executive systems) are “goal-directed” systems that allow an agent to consider the possible consequences or outcomes of its actions to guide behavior. Habit systems mediate behaviors that are triggered in response to certain stimuli or situations but without consideration of the consequences.

“Habit” systems do not mean we are calling addiction is a habit, it simply means behaviour is automatic, ingrained, individuals respond immediately, without future consequence to certain stimulus, such as stress or emotional distress. It is a conditioned response!

Brain areas underlying these conditioned or Pavlovian responses include the amygdala, which identifies the emotional significance or value of external stimuli, and the ventral striatum, which mediates motivational influences on instrumental responding (22), and their connections to motor circuits (23).

Thus, it has been argued that emotions constitute a decision-making system in their own right, exerting a dominant effect on choice in situations of opportunity or threat (24).

It should be noted here, that in the addiction cycle, as it progresses towards endpoint addiction and compulsive use of substances, there is a stress based reduction in prefrontal cognitive control over behaviour, and a responding more based on automatic emotive-motoric regions of the brain such s the dorsal striatal (DS) (and basal ganglia). Reward processing moves to the DS also from the ventral striatum (VS).

Thus stress modulates instrumental action in favour of the DS-based habit system at the expense of the PFC-based goal-directed system, also seen in hypertrophy of the DS and hypotrophy of the PFC.

This shift from cognitive to automatic is also the result of excessive engagement of habitual processes, by partly by affecting the contribution of multiple memory systems on behaviour. We suggest that emotional stress via amgydaloid activity knocks out the hippocampal (explicit) memory in favour of the DS which is also a memory system, that of implicit memory, the procedural memory.

In lien with addiction severity, the brain appears to implode inwards towards compulsive behaviours of sub-cortical areas such as the DS modulated by the amgydala from more conscious cognitive control areas of the cortex. In fact, it is possible to say that this conscious cognitive control diminishes.

Recent evidence suggests this role of stress in shifting goal-directed control to habitual control of behavior (25). This effect appears to be mediated by the action of both cortisol and noradrenaline (26).

More importantly, perhaps for our argument is that , this shift from hippcampal to DS memory is also a function of a “emotional arousal habit bias”, as seen in post traumatic stress disorder, via amgydaloid hyperactivity, or distress based hyperactivity, which results in emotional distress acting as a stimulus to the automatic responding of the DS. Affect related behaviour, in essence, becomes more compulsively controlled also.

In simple terms, negative urgency, may bias an automatic responding towards amgydaloid activation of the dorsal striatum and away from cortical areas such as the ventromedial cortex – vmPFC (27 ) which is involved in emotionally guided decision making and this may have consequence for decision making as decision making involves responding to stimulus such as emotionally provoking stimuli.

One study (28) showed this vmpfc to be hyperactive in recently abstinent alcoholics, perhaps as the result of altered stress systems which create a state called allostasis, and when further stressed responding moved to the more compulsive regions of the brain listed above. This suggest to us, that there are inherent difficulties with emotional dysregulation, particularly in early abstinence/recovery and that these resources when taxed further by seemingly stressful decision making may be dealt with via a need to make a decision to relieve this “distress” feeling rather than achieve a long term outcome. Relieving this distress is thus the outcome most urgent.

Thus for some alcoholics there is an overtaxing of the areas implicated in emotional regulation and thus emotionally guided decision making and under extreme stress we suggest this switches to more a more compulsive decision making profile.

The habit system chooses actions based upon stored associations of their values from past experience; through training, an organism learns the best action to take in a certain situation. Upon recognition of the situation again this “best action” will automatically be initiated, without consideration of consequences of such an action. This process is very fast but inflexible, unable to adapt quickly to changes in the value of outcomes (29,30).

Thus although emotion can guide decision-making when it is integral to the task at hand, emotional responses that are excessive can be detrimental (31).

Dorsal prefrontal regions are also involved in the regulation of affective states (32). Excessive emotion is likely to require increased regulation by these areas (33,34).

Dorsal prefrontal regions are additionally important in decision-making and inhibitory control, thus high levels of emotion that require regulation may limit resources available for these functions, which may contribute to deficits in decision-making.

As we mentioned this PFC control becomes impaired in the addiction cycle with automatic responding becomes more prevalent. This is especially the result of the emotional manifestation of chronic stress which is distress. We suggest this distress can act as a switch between conscious and automatic (unconscious) responding and this has consequences for decision making.

Given the crucial role of emotions in the processes of decision-making as described above, it follows that dysregulation of emotional processing may contribute to the observed decision-making deficits observed in substance dependent individuals. Decisions are driven by distress or negative affect and appear to favour now over then/later.

Looking Inside the Brain

A consistent finding of neuroimaging studies of decision-making in substance dependence is hypoactivation of the prefrontal cortex (35-37),

Chronic drug use is consistently associated with VPFC, DLPFC and antior cingulate or ACC gray matter loss in cocaine and alcohol dependence (38-42) and reduced prefrontal neuronal viability in opiate dependence (43,44). VPFC and DLPFC loss have been shown to predict both impaired performance on the IGT (45) and preference for immediate gratification in delay discounting tasks (37)

These areas and others involved in emotional regulation such as the hippocampus, orbitofrontal cortex and insula show morphological abnormalities and the emotional regulation neural network as a whole appears to have functionality and connectivity impairments.

These all suggest emotions are not being utilized properly to guide decisions. This may even appear as unregulated and distressing with the brain experiencing this distress rather than processed emotions.

A similar decision making profile is seen in alexithymia, where there is a difficulty labelling and processing emotions and thus using them to guide decision making which appears to result in recruitment of more compulsive or motor expressive areas of the brain outlined here. There are also similar morphological, neurobiological and connectivity impairments as seen in addiction. Cocaine addicts also have a similar decision making profile as do children of alcoholics, before they start to use substances.

Whether these separate groups all have distress prompting this decision making profile or whether it is unpleasant feeling state based on not fully processing emotion is open to debate.

As the prefrontal regions of the planning system are impaired in substance dependence, this compromises both the ability to generate affective states relating to long term goals and the ability to exert executive inhibitory control over drug-seeking thoughts and actions .

Dorsal prefrontal regions are involved in the regulation of affective states . Therefore excessive anxiety would require increased regulation by these areas. Studies have shown dorsal prefrontal regions to be important in regulating reducing amygdala activity . Considering these prefrontal regions are important for decision-making and anxiety regulation would limit the resources available for effective decision-making within the planning system and would not be able to inhibit more amgydaloid, or compulsive responding.

Bechara concluded that an impaired ability to use affective signals to guide behavior underlie impaired decision-making in these individuals. We forward the idea that distress signals guide this decision making and behaviour via a compulsive desire to automatically act to relieve a distress state. Whether via an unprocessed emotional state or as the consequence of the addiction cycle and excessive chronic distress recruiting compulsive parts of the brain.

Either way emotional processing and regulation deficits lie at the heart of these decision making difficulties!

Now is chosen instead of later, short term gains rather than long term higher gains, because of the negative urgency to act now, to relieve a distress, which automatically, not consciously, devalues future outcome.

The future is now in other words.

There is a distress based urgency to act this moment, not later. It is this desire to compulsively act which may give rise to obsessive compulsive behaviours, based on the desire to relieve distress not on the relative merits of a future consequence.

It can appear as a “little emergency” not a choice, the “flight or fight” response that delay discounting could possible be measuring and that excessive noradrenaline and glucocorticoids (stress chemicals) prompt – it has to be done, needs to be done now!

References (to be included)

1 Hommer D. W., Bjork J. M., Gilman J. M. (2011). Imaging brain response to reward in addictive disorders. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1216, 50–61 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05898.x

2. de Wit H. (2009). Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict. Biol. 14, 22–31 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x [PMC free article]

3. Dalley J. W., Everitt B. J., Robbins T. W. (2011). Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron 69, 680–694 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.020

4. Shin S. H., Hong H. G., Jeon S. M. (2012). Personality and alcohol use: the role of impulsivity. Addict. Behav. 37, 102–107 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.006 [PMC free article]

5. Verdejo-Garcia A., Bechara A., Recknor E. C., Perez-Garcia M. (2007a). Negative emotion-driven impulsivity predicts substance dependence problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 91, 213–219 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.025

6. Aron A. R. (2007). The neural basis of inhibition in cognitive control. Neuroscientist 13, 214–228

7. Bickel W. K., Miller M. L., Yi R., Kowal B. P., Lindquist D. M., Pitcock J. A. (2007). Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 90Suppl. 1, S85–S91 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016

8. Madden G. J., Bickel W. K., Jacobs E. A. (1999). Discounting of delayed rewards in opioid-dependent outpatients: exponential or hyperbolic discounting functions? Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol.7, 284–293 10.1037/1064-1297.7.3.284

9. Kirby K. N., Petry N. M., Bickel W. K. (1999). Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 128, 78–87 10.1037/0096-3445.128.1.78

10. Petry N. M. (2001). Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 154, 243–250

11. Bechara A., Damasio A. R., Damasio H., Anderson S. W. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition 50, 7–15

12. Bechara A., Damasio H. (2002). Decision-making and addiction (part I): impaired activation of somatic states in substance dependent individuals when pondering decisions with negative future consequences. Neuropsychologia 40, 1675–1689 10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00015-5

13. Kirby K. N., Petry N. M. (2004). Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction 99, 461–471 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x

14. Coffey S. F., Gudleski G. D., Saladin M. E., Brady K. T. (2003). Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 11, 18–25 10.1037/1064-1297.11.1.18

15. Petry N. M. (2001). Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 154, 243–250

16. Bjork J. M., Hommer D. W., Grant S. J., Danube C. (2004a).Impulsivity in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients: relation to control subjects and type 1-/type 2-like traits. Alcohol 34, 133–150

17. Mitchell J. M., Tavares V. C., Fields H. L., D’Esposito M., Boettiger C. A. (2007). Endogenous opioid blockade and impulsive responding in alcoholics and healthy controls.Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 439–449 10.1038/sj.npp.1301226

18. Koob G. F., Le Moal M. (2005). Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the ‘dark side’ of drug addiction. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1442–1444 10.1038/nn1105-1442

19. Stewart J. (2008). Review. Psychological and neural mechanisms of relapse. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 3147–3158 10.1098/rstb.2008.0084 [PMC free article]

20. Lemenager T., Richter A., Reinhard I., Gelbke J., Beckmann B., Heinrich M., et al. (2011). Impaired decision making in opiate addiction correlates with anxiety and self-directedness but not substance use parameters. J. Addict. Med. 5, 203–213 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31820b3e3d

21. Zhang X. L., Shi J., Zhao L. Y., Sun L. L., Wang J., Wang G. B., et al. (2011). Effects of stress on decision-making deficits in formerly heroin-dependent patients after different durations of abstinence. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 610–616 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040499

22. Cardinal R. N., Parkinson J. A., Hall J., Everitt B. J. (2002).Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 26, 321–352 10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00007-6

23. van der Meer M., Kurth-Nelson Z., Redish A. D. (2012).Information processing in decision-making systems.Neuroscientist 18, 342–359 10.1177/1073858411435128

24. Seymour B., Dolan R. (2008). Emotion, decision making, and the amygdala. Neuron 58, 662–671 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.020

25. Schwabe L., Wolf O. T. (2011). Stress-induced modulation of instrumental behavior: from goal-directed to habitual control of action. Behav. Brain Res. 219, 321–328 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.12.038

26. Schwabe L., Tegenthoff M., Hoffken O., Wolf O. T. (2010).Concurrent glucocorticoid and noradrenergic activity shifts instrumental behavior from goal-directed to habitual control. J. Neurosci. 30, 8190–8196 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0734-10.2010

27. Cyders, M. A., Dzemidzic, M., Eiler, W. J., Coskunpinar, A., Karyadi, K., & Kareken, D. A. (2013). Negative Urgency and Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Responses to Alcohol Cues: fMRI Evidence of Emotion‐Based Impulsivity.Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

28. Seo, D., Lacadie, C. M., Tuit, K., Hong, K. I., Constable, R. T., & Sinha, R. (2013). Disrupted ventromedial prefrontal function, alcohol craving, and subsequent relapse risk. JAMA psychiatry, 70(7), 727-739.

29. Daw N. D., Niv Y., Dayan P. (2005). Uncertainty-based competition between prefrontal and dorsolateral striatal systems for behavioral control. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1704–1711 10.1038/nn1560

30. Redish A. D., Jensen S., Johnson A. (2008). A unified framework for addiction: vulnerabilities in the decision process.Behav. Brain Sci. 31, 415–437 discussion: 437–487. 10.1017/S0140525X0800472X [PMC free article]

31. Bechara A., Damasio A. R. (2005). The somatic marker hypothesis: a neural theory of economic decision. Games Econ. Behav. 52, 336–372

32. Phillips M. L., Drevets W. C., Rauch S. L., Lane R. (2003a).Neurobiology of emotion perception I: the neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 504–514 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00168-9

33. Amat J., Baratta M. V., Paul E., Bland S. T., Watkins L. R., Maier S. F. (2005). Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus.Nat. Neurosci. 8, 365–371 10.1038/nn1399

34. Robbins T. W. (2005). Controlling stress: how the brain protects itself from depression. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 261–262 10.1038/nn0305-261

35. Bolla K. I., Eldreth D. A., London E. D., Kiehl K. A., Mouratidis M., Contoreggi C., et al. (2003). Orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction in abstinent cocaine abusers performing a decision-making task. Neuroimage 19, 1085–1094 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00113-7 [PMC free article]

36. Tanabe J., Thompson L., Claus E., Dalwani M., Hutchison K., Banich M. T. (2007). Prefrontal cortex activity is reduced in gambling and nongambling substance users during decision-making. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28, 1276–1286 10.1002/hbm.20344

37. Bjork J. M., Momenan R., Smith A. R., Hommer D. W. (2008b). Reduced posterior mesofrontal cortex activation by risky rewards in substance-dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 95, 115–128 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.014[PMC free article]

38. Fein G., Di Sclafani V., Meyerhoff D. J. (2002b). Prefrontal cortical volume reduction associated with frontal cortex function deficit in 6-week abstinent crack-cocaine dependent men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 68, 87–93 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00110-2[PMC free article]

39. Makris N., Gasic G. P., Kennedy D. N., Hodge S. M., Kaiser J. R., Lee M. J., et al. (2008). Cortical thickness abnormalities in cocaine addiction-a reflection of both drug use and a pre-existing disposition to drug abuse? Neuron 60, 174–188 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.011 [PMC free article]

40. Fein G., Shimotsu R., Barakos J. (2010). Age-related gray matter shrinkage in a treatment naive actively drinking alcohol-dependent sample. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 34, 175–182 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01079.x [PMC free article]

41. Goldstein R. Z., Volkow N. D. (2011). Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 652–669 10.1038/nrn3119 [PMC free article]

42. Ersche K. D., Turton A. J., Pradhan S., Bullmore E. T., Robbins T. W. (2010b). Drug addiction endophenotypes: impulsive versus sensation-seeking personality traits. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 770–773 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.015 [PMC free article]

43. Haselhorst R., Dursteler-MacFarland K. M., Scheffler K., Ladewig D., Muller-Spahn F., Stohler R., et al. (2002).Frontocortical N-acetylaspartate reduction associated with long-term i.v. heroin use. Neurology 58, 305–307

44. Yucel et al.,2007Haselhorst R., Dursteler-MacFarland K. M., Scheffler K., Ladewig D., Muller-Spahn F., Stohler R., et al. (2002).Frontocortical N-acetylaspartate reduction associated with long-term i.v. heroin use. Neurology 58, 305–307

45. Tanabe J., Tregellas J. R., Dalwani M., Thompson L., Owens E., Crowley T., et al. (2009). Medial orbitofrontal cortex gray matter is reduced in abstinent substance-dependent individuals. Biol. Psychiatry 65, 160–164 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.030[PMC free article]

46. Murphy, A., Taylor, E., & Elliott, R. (2012). The detrimental effects of emotional process dysregulation on decision-making in substance dependence. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 6.

LeDoux J. (2007). The amygdala. Curr. Biol. 17, R868–R874 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.005

LeDoux J. (2012). Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron 73, 653–676 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.004 [PMC free article]

LeDoux J. E. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 155–184 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155