When I first came into recovery I would be plagued by intrusive thoughts about drinking, I would have thoughts about drinking, at certain times of the day in particular, on sunny days etc.

These thoughts used to greatly distress me and I would end fighting with these thoughts which only seemed to make things worse, the thoughts seem to increase rather than decrease and I got increasingly distressed.

I had no control over these thoughts and would get into a terrible emotional state over this. All before I decided it was now a good time to ring my sponsor. I always waited until I was in as much emotional pain as possible before ringing my sponsor!

I thought I could go it alone – that I did not need any help. I was in control of this.

Geez, surely I could control my own thoughts for flips sake!

Hmmm…afraid not!?

In early recovery I was as powerless over thinking as well as my drinking.

It was obvious I had lost control of my thinking like my drinking – it took a lot longer (and I still forget this even today!) to realise I have no control over my thinking.

It chatters away regardless of my will, my wishes. It I have found is not usually a friend.

So like everything else in recovery I decided to research this! To find out why my thinking seemed out to get me, to negatively affect my recovery. To find out why my thinking did not seem to help me in recovery.

I found out that the idea that abstinence will automatically also decrease alcohol-related intrusive thoughts had been dismissed by research and vast anecdotal evidence.

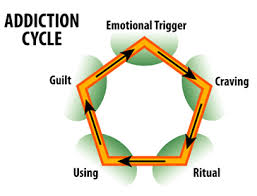

Practically all therapies for alcoholism e.g AA, SMART and so on suggest that urges create automatic thoughts about drinking.

This has been demonstrated in research that distress automatically gives rise to intrusive thoughts about alcohol. (1) This reflects emotional dysregulation as these intrusive thoughts are correlated to emotional dysregulation (2).

These thoughts to the recovering/abstinent individual can be seen as egodystonic which is a psychological term referring to behaviors, values, feelings that are not in harmony with or acceptable to the needs and goals of the ego, or consistent with one’s self image.

Other conditions, such as OCD, have these egodystonic thoughts creating the distress that drives a compulsive need to act on them, rather than letting them pass.

In other words, these thoughts are seen as distressing and threatening and compel one to act to reduce this escalating sense of distress. A similar process can happen to those in early recovery.

Thoughts about drinking or using when you now wish to remain in recovery are egodystonic, they are contrary to the view of oneself as a person in recovery. The main problem occurs when we think we can control these thoughts are that these thoughts mean we want to drink or are going to relapse!

Early recovery is a period marked by heightened emotional dysregulation and the proliferation of intrusive thoughts about alcohol .

In fact, research demonstrates that alcohol-related thoughts can resemble obsessive-compulsive thinking (3,4).

In fact, one way to measure “craving” in alcoholics is by scale called the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (5) , thus highlighting certain similarities between alcoholism and OCD.

This finding is also supported by clinical observation and leads to the expectation that among abstinent alcohol abusers, alcohol-related thoughts and intrusions are the rule rather than the exception (6)

Relatively little is known about how alcohol abusers appraise their alcohol-related thoughts. Are they aware that alcohol-related thoughts occur naturally and are highly likely during abstinence?

Or do they interpret these thoughts in a negative way, for example, as unexpected, shameful, and bothersome? Misinterpretations of naturally occurring thoughts or emotional reaction to them may be detrimental for abstinence (7).

A number of papers and studies have shown that individuals’ appraisal of their intrusive thoughts as detrimental and potentially out of their control may lead them to dysfunctional and counterproductive efforts to control their thinking.

Alcohol-related thoughts cause an individual to experience strong emotional reactions; however, alcohol abusers will increase their efforts to control their thinking only when they have negative beliefs about these thoughts.

For instance, spontaneous positive memories about alcohol (‘‘It was so nice to hang out at parties and to drink with my buddies’’) may be appraised—and misinterpreted—as ‘‘the first steps toward a relapse’’.

Such an appraisal of one’s thoughts about alcohol as problematic may instigate thought suppression and other efforts to control the thoughts.

These efforts must be assumed to be counterproductive and will increase rather than prevent negative feelings and thoughts, and they may even demoralize alcohol abusers who are trying to remain abstinent

On the other hand if positive alcohol-related thoughts are not appraised as problematic but as a normal part of abstinence, the awareness of these thoughts might even lead to the selection of more adaptive coping responses, which could help to reduce the risk of relapse, such as talking to someone about them or just simply letting these thoughts go.

In one study (8), participants who reported on their thoughts about alcohol in the previous 24 hours, 92% reported experiencing at least some thoughts about drinking that ‘‘just pop in and vanish’’ without an attempt to eliminate them. This suggests that if both suppression and elaboration can be avoided, many intrusive thoughts will be relatively transient.

An “accept and move on’’ strategy provides an opportunity for the intrusion to remain a fleeting thought.

In other words, just let go.

This means the thoughts go, and the distress which activates them, too.

This is recovery a lo of the time. Getting embroiled in thinking and then letting go, repeat…

That is why helping others is important -it takes us out of our crazy heads

References

1. Zack, M., Toneatto, T., & MacLeod, C. M. (1999). Implicit activation of alcohol concepts by negative affective cues distinguishes between problem drinkers with high and low psychiatric distress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(3), 518.

2. Ingjaldsson, J. T., Laberg, J. C., & Thayer, J. F. (2003). Reduced heart rate variability in chronic alcohol abuse: relationship with negative mood, chronic thought suppression, and compulsive drinking. Biological Psychiatry, 54(12), 1427-1436.

3. Caetano, R. (1985). Alcohol dependence and the need to drink: A compulsion? Psychological Medicine, 15(3), 463–469

4. Modell, J. G., Glaser, F. B., Mountz, J. M., Schmaltz, S., & Cyr, L. (1992). Obsessive and compulsive characteristics of alcohol abuse and dependence: Quantification by a newly developed questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 16(2), 266–271.

5. Anton, R. F., Moak, D. H., & Latham, P. (1995). The Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale: A self-rated

instrument for the quantification of thoughts about alcohol and drinking behavior. Alcoholism:

Clinical and Experimental Research, 19, 92–99.

6. Hoyer, J., Hacker, J., & Lindenmeyer, J. (2007). Metacognition in alcohol abusers: How are alcohol-related intrusions appraised?. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31(6), 817-831.

7. Marlatt, G. A., & Gordon, J. R. (Eds.). (1985). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the

treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press

8. Kavanagh, D. J., Andrade, J., & May, J. (2005). Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: the elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychological review, 112(2), 446.