Science as we have shown in many blogs has given us unprecedented insight into brain mechanisms implicated in addiction. It has shown us how various neural networks governing reward/motivation, memory, attention and emotions seem to be usurped in the addiction cycle.

Important aspects of “the self” are taken over in other words. It has shown how those vulnerable to addiction seem to have decision making deficits, suffer impulsivity, choose now over later, do not tolerate distress or negative emotions etc. Over react to life!!

It shows how addicts have difficulties in regulating stress, and that stress systems in the brain are altered to such an extent that they rely for brain function on allostasis not homeostasis.

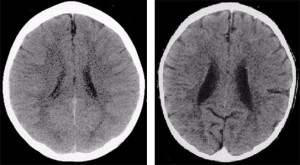

They show us that various neurotransmitters are also reduced in the addict’s brain such as GABA, the inhibitors or brakes of the brain. We are deficient in natural opioids, dopamine, serotonin etc. Our brains are different to “normies” to “earthlings.

Science suggests the majority of addicts have had abuse or trauma, neglect or adverse experiences while in childhood and this too contributes to addiction vulnerability via stress and emotion dysregulation and a heightened sensitivity to the stimulating effects of drink, drugs and certain behaviors such as eating, sex, gambling, gaming, internet use etc.

Science also offers suggestions on treatment. It offers the use of chemicals or antagonists to reduce “carving” and it suggest the effectiveness of CBT, Mindfulness and DBT but it seems to know little about how or why 12 step programs work.

Science can’t quite bring itself to believe that laypeople, fellow addicts, can help solve each others’ problems. It scratches it’s head about “spiritual maladies” and “spiritual solutions”; how the 12 steps could bring about such a cathartic change in personality to change someone from a hopeless addict to a person in recovery.

It wonders how helping others and taking fearless and honest inventory can bring about the psychic change sufficient to help some with addiction recover. To be restored to sanity.

In various blogs we have suggested the spiritual malady can also be viewed as a emotional disease and that the 12 steps also allow us to process emotions and regulate feelings in a way we could not before.

It helps us process the many negative emotions of the past via steps 4-9 and sets us free by consigning these emotions to long term memory instead of having them swirl around forever in explicit memory, forever tormenting us.

For us, 12 step programs offer a workable definition of the addict. The “spiritual malady” mentioned in the Big Book does however refer to all people, not just alcoholics/addicts, and is borrowed directly from the Oxford Group. But reading around this, there are many examples of emotional and stress dysregulation in the BB, some 70 plus examples in the first 164 pages of how our emotions dominated us and how we were shot through with fear.

It is the description of alcoholics in the BB that highlights we have an emotional as well as spiritual disease. What is a spiritual disease if not manifest in negative emotional states such as resentments, false pride, anger, jealousy, and so on. The need to control, to be better than, to know best, all also signs of emotional immaturity. The BB clearly show us alcohol(ism) has made us very emotional irresponsible. We step on the toes of our fellows and they retaliate.

We have a spiritual malady but, from descriptions of ourselves, it seem more extreme than normal people. It is not only in terms of alcohol that “the delusion that we are like other people, or presently may be, has to be smashed.”

The definition is thus workable because it allows one to act in relation to it. For example, if I am aware of the nature of my defects of character I am in effect aware of what cuts me off from the “sunlight of the spirit”, aware of what keeps me spiritually and emotionally ill, what keeps me in a state of unprocessed emotions, of emotional dysregulation, of undealt with distress. Of what keeps me in resentment in a viscous circle of unprocessed negative emotions.

It shows me how this dysregualtion effects other people and gives me the tools to correct my mistakes, to make amends for the mistakes I have made. To relieve distress. It gives me a framework, a program of action which allows me to live with others, on life’s terms, although I might not immediately agree with those terms, which is often the case!

It gives me a choice that I never had before. It says to me you can live with unregulated negative emotions and cultivate your misery or you can choose to use the program to free yourself from these negative unregulated emotions and by processing them be restored to to sanity. It can help me get out of the past/future and into the now, the present.

The solution to my spiritual and emotional malady is this simple. Identify, label, verbalise either to God or to another human being the nature of these wrongs/sins/defects/shortcoming/negative emotions – those factors that trapped me in self propelled distress – and they are quite simply removed. That is my experience. Honesty, openness, willingness, the how of getting out of self. Repeatedly during the day. When I do not do this I suffer emotionally, and others suffer too.

The steps allow me to reduce my distress and this control of distress and stress via the cultivation of serenity, balance, selflessness deactivates my illness for a while allows me to be happy, joyous and free as this appears to be the state of freedom from self, in my experience, this seems to be a state of Grace in other words. The sunlight of the spirit that Bill W mentioned.

It is the solution. I drank to get away from myself. To exhale some air and go “phew!” I do not not have to even consider that now because I can do that via the steps, by simply taking inventory and letting go. It is our emotions that hold on to negative thoughts, that grow them in the dark shadow of our souls like fungus. Honesty is a light that extinguishes them. By letting go, by allowing my emotions to lower in intensity, to label and identify them and thus allow via, God’ loving Grace, for them to be removed (and stored away where they belong in long term memory).

But there are so many more reasons why 12 step programs work! If the majority of us have had abusive upbringings then it suggests perhaps that there are attachment issues present in many of us. For me my insecure attachment to my primary care giver, my mother, may have caused an insecure attachment which has certainly kick started my later addictions. In fact some observers have gone so far as to view addiction as an attachment disorder.

I will blog on this in the next weeks or two. I will blog on this attachment disorder as perhaps causing that “hole in the soul” that many addicts talk about in meetings.

That not belonging, being separate from. That isolation – these may all stem from insecure attachment. Insecure attachment can shape the brain in a way that makes it difficult to regulate stress and emotion and thus contribute to later addiction. It may cause the differences in emotions mentioned above. It may also point to heart of the problem and why 12 steps groups work in treating addiction.

12 step groups seem to directly treat the “Hole in the soul” by instantly giving an addict a sense of belonging which is particularly powerful after many years in the desolation of addiction. I know that I stayed in AA because I have finally found the club, the tribe, that I belong too. This like other families is a group of people I love, but sometimes have problems with, fall out with, return to and see in a new light. It is an organic relationship. It has never been wonderful at all times but that says as much about me and my distrust of others, my insecure attachment as it does AA.

I had grown up not even feeling part of my family. The required psychic change happened to me in my first meeting I believe. Others have commented on how I walked into the meeting a different person from the person who left the meeting. I had a spiritual experience of some sort in my first meeting, purely through identifying with the other recovering alcoholics in the meeting. Not about their drinking, but by identifying with their spiritual malady. I identified with there emotional disease and I realised that if they could find a solution then there was a chance, however small, that I could too. The first flickers of hope happened in that very first meeting.

I knew in my heart I had somehow returned home in a strange way. I had found my surrogate family, those who would help love me back to health and recovery.

Perhaps this is what Science is generally not getting about 12 step groups, the powerful therapeutic tool of talking with someone who has been where you have, who shares your disease and who can help you recovery, as they have. Even now sitting in an AA meeting is the most spiritual thing I do. More so that attending Chapel, visiting monks in isolated monasteries.

Identification with those in the same boat as you is profound. It tells you are not alone. It tells you I need to help you to help me. We are in this together, not you and I. Us, together.

It accepts you as you are, at your lowest ebb, at your rock bottom, your most degraded self. It offers your affection when you are your most unlovable, most wretched.

This for me was the key, being accepted into a group I knew I belonged in. My new home. My new secure attachment. I believe this secure attachment and the love you have for fellowships, sponsees and the love you can now show yourself and your family and friends and people in your life is that solution. To Love and be loved.

I felt in my active addiction I was not deserving of love, that you shouldn’t give me your love. I didn’t know how to give you mine. Now I have so much love inside of me. It is this love that has filled up the hole in my soul.

Okay, it has also increased my natural opioids, raised my dopamine via belonging, raised the GABA brakes in my brain. It has also increase my serotoninergic well being and happiness, it has lower my excitatory glutamate. It has restored more neuro-chemical balance in my head. By prayer and mediation and helping others it restores sanity, fleeting periods of homeostasis, balance, serenity. It most importantly reduces stress/distress, silences my addiction, long enough for me to think of others, help others. And there is not greater buzz that helping others. Love is the drug that I have been thinking off. Love is the solution.

Trust someone enough so that you can begin to allow them and God to love you and you will eventually love them back. A whole new world, full of love and being whole awaits.

The journey is from the crazy head to the serene heart.