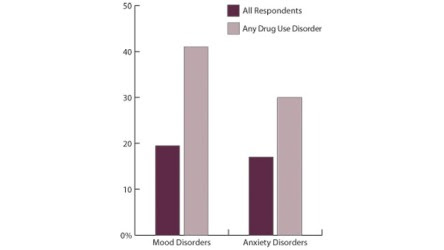

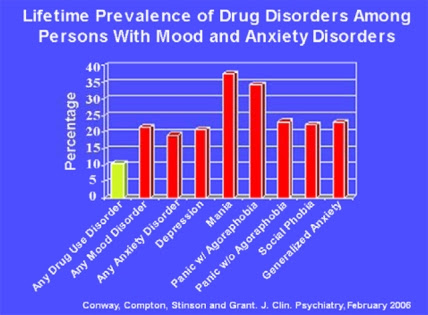

In this blog we have repeatedly queried whether the co-occurrence of so-called co-morbidities with substance use disorders (SUDs) is as high as reported in many studies (1).

In a blog from yesterday Are most co-morbidities really substance-induced disorders? that diagnosis is often flawed in many studies and that the so-called diagnosis of co-morbidity is not borne out long term with many presumed co-morbid disorders disappearing in time.

In an recurring example given, the author uses the high prevalence of so-called comorbidity with mood disorders to illustrate how alcoholics and addicts appear to have a similar range of mood disorders as that of a normal population sample, i.e. as normally in society, around 15%.

This is in keeping with our ancedotal evidence of attending numerous AA meetings over a number of years has shown that in the vast majority of individuals the symptoms of a supposedly co-morbid disorder such as General Anxiety Disorder (GAD) or major depression (MD) appear to dissipate after some weeks.

This either means that there 12 step program of recovery outlined in mutual support groups like AA can provide profound therapeutic effect on other disorders (which they very well may do) or that the co-morbidities highlighted in many studies is greatly exaggerated.

This exaggeration has two major consequences. The study of and research into SUDs is hampered by relegating affective dimensions to that of co-morbidity while not exploring the specific emotional dysregulation at the heart of SUDs ( in particular dyscontrol over subcortical/amgydaloid emotional responding appears at the heart of most of these psychopathologies so they have common neural substrates and mechanisms but they may not manifest in the same behavioural responses – in other words there may be common emotional dysregulatory mechanisms but different pathomechanisms)

That is not to say that co-occuring disorders can not exaggerate the trajectory of a SUDs as disorders such as post traumatic stress disorders may, for example, add to distress based responding and may also require further and more specific treatment in addition to that for a SUD.

Also research needs to not only to predict behaviour e.g. in the case of addiction, relapse, but also to help prevent conditions arising. Thus it is imperative that research more fully informs prevention and intervention in children and adolescents at risk from later SUDs.

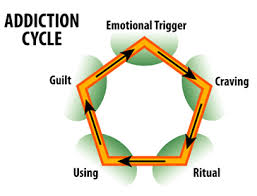

Thus the specific aspects of emotional dysregulation specific to a SUD such as, for example, a tendency to act rashly or impulsively under distress may be addressed by considering whether this is also the function of emotional processing deficits which mean emotions are “avoided” rather than processed by cortical areas, resulting in more reactive sub-cortical responding which has consequence for a decision making profile which is more based on alleviating this distress state, this unpleasant feeling state, than it does the recruiting via effective emotional processing and regulation of more cortical areas of the brain. All of which has ramifications for a more accurate study of the aetiology of addiction per se and it’s prevention.

For example, teaching at risk children how to identify, label, and verbalise their emotions at an early age will help them learn how to process and regulation them; to then use these feeling states to guide goal-directed adaptive behaviour rather than and recruiting more subcortical emotive-motor parts of the brain to flee these distress states resulting in more reactive decision making and emotional management. It would also help with reducing the effect that initial alcohol use has on adolescents as emotional dysregulation potentiates reward, so distress/stress make the rewarding effects of drugs and alcohol heightened. It may also mean heart rate variability is also higher so that the smoothing, calming effects of alcohol are not as exaggerated. It would help put some neural brakes on increasingly out of control behaviour.

It would help tackle the premorbid distress at the heart of vulnerability to later addiction at its source, its manifestation as emotional reactivity.

It would return us to a theoretical conception of addicts as suffering human beings not neurobiological machines, which can be tweeked by this neurochemical or that!

This leads me onto the second short point. If we relegate the anxiety, impulsivity mood and affective dimensions of a SUD to co-morbidity we limit our understanding of the overlapping and interlinked roles of emotional processing and regulation deficits on reward processing for example.

There is a tendency in some researchers to see addiction purely in terms of neurbiological processes, usually dopaminergic, equating addiction to the effects that a drug or alcohol has on the neurobiology and neuro-anatomy of the brain, and not to see how these deficits may not be simply drug induced but also linked to stress dysregulation which itself is linked profound and pre-existing impairments in emotion processing and regulation.

A chronic addict is emotionally distressed most of the time, who do dopaminergic models explain this emotional response or the fact that most relapse is stress or emotional distress based and prompted.

Or the effects of maltreatment or abusive childhoods, or economic deprivation or deviant peers. Observing addiction as a inherited emotional regulation and processing deficit, exaggerated by sometimes dysfunctional parenting (especially if the parents are also addicts and alcoholics) and persistent stress allows us to observe how genes in certain individuals are influenced by environment and manifest in behavioural undercontrol, emotion lability and reactivity and impaired, impulsive decision making in those at risk from later addiction. It may be important to study what is impaired before the neurotoxic effects of chronic drug and alcohol use profoundly aggravate these “pre-morbid” impairments.

To conclude, there is “overlap of the biological substrates and the neurophysiology of addictive processes and psychiatric symptoms associated with addiction”

Pani et al suggest the “inclusion of specific mood, anxiety, and impulse-control dimensions in the psychopathology of addictive processes.”

We suggest these can be accommodated under the umbrella of emotional regulation and processing deficits as the above and additional deficits seen in alcoholics and addicts are more satisfactorily covered by this nosology.

We agree with Pani et al, that “addiction reaches beyond the mere result of drug-elicited effects on the brain and cannot be peremptorily equated only with the use of drugs despite the adverse consequences produced.”

We infer that emotional dysregulation is at the “very core of both the origins and clinical manifestations of addiction and should be incorporated into the nosology of the same, emphasising how addiction is a relapsing chronic condition in which psychiatric manifestations play a crucial role.”

We agree that “addictionology cannot be severed from its psychopathological connotations, in view of the undeniable presence of symptoms, of their manifest contribution to the way addicted patients feel and behave, and to the role they play in maintaining the continued use of substances.”

References

Pani, P. P., Maremmani, I., Trogu, E., Gessa, G. L., Ruiz, P., & Akiskal, H. S. (2010). Delineating the psychic structure of substance abuse and addictions: Should anxiety, mood and impulse-control dysregulation be included?. Journal of affective disorders, 122(3), 185-197.